UPDATE: On May 3, Ecology and the shellfish growers cancelled the pesticide spraying permit. Read the news release here.

We have heard from many people who read the recent Seattle Times column (and other articles) about a permit for imidacloprid use in Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor. We want to make sure you have the facts about the permit, the pesticide (and the label you’ve read about), and to set the record straight about our role.

We monitor, analyze and plan ways to clean and protect the state’s waters. This involves limiting and restricting the ways facilities, farms and others discharge any pollution into the waterways.

Two weeks ago we issued a water quality permit to the Willapa – Grays Harbor Oyster Growers Association for the use of imidacloprid – a widely used, common pesticide – on commercial shellfish beds in Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor. This is one of many aquatic pesticide permits we issue to ensure water quality is maintained during use of a pesticide to combat invasive species, mosquitoes, algae, or in this case, burrowing shrimp.

About burrowing shrimp

Burrowing shrimp are a native species to Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor. As their name suggests, they burrow into the mud in tidelands, loosening mud, causing it to soften and lose its integrity. For shrimp, that’s a good thing. But for an oyster or clam it means they’ll likely sink into the mud and suffocate. About 25 percent of our nation’s commercial oysters are produced from these two bays. The shrimp are more than a nuisance; they put the shellfish industry and economy at risk.

Shellfish growers have been combating the burrowing shrimp for more than 50 years

From the 1960s until 2013 a pesticide called carbaryl was used in these same areas.

Ecology permitted the use of carbaryl in 2002, monitoring its impacts on water quality. In 2008, the shellfish industry began pursuing a less toxic way of controlling the burrowing shrimp population. A wide number of options were considered and tested, including:

- Covering tideflats with gravel and shells

- Organic insecticides such as:

- Mustard seed meal

- Habanero pepper extract

- Garlic oil

- Running all-terrain vehicles over shellfish beds to compact and cave-in burrows

- Propane explosions within the infested mudflats

- Injecting clay slurry into burrows

- Electroshocking the mudflats

- Releasing high-pressure sound waves into the mudflats

- Alternative shellfish culture systems

- Plastic mesh barriers

- Other chemicals

The most effective method

It turns out that the most effective way to combat the burrowing shrimp was with imidacloprid, one of the most commonly used agricultural pesticides. It’s the active ingredient in most flea collars for your pets, is used on termites, and protects fruits and vegetables from insects that damage crops.

It works by causing paralysis in an organism, like burrowing shrimp. It prevents them from being able to move, causing eventual death. It’s most effective against invertebrates, like the burrowing shrimp. It’s far less of a threat to fish or other, larger, vertebrate wildlife, like birds and humans.

But what about the label saying you can’t use it on water?

Every pesticide is registered for a particular use. The bottle or package of imidacloprid consumers can buy at their local hardware store or garden center has been registered for use on land, not the water. The household label states that. That’s the type of imidacloprid the Seattle Times’ columnist wrote about.

However, the product permitted for use in Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor to control burrowing shrimp in commercial shellfish beds is a different product with a different label.

Limited use

For this permit, shellfish growers are limited to using imidacloprid only on commercial shellfish beds on no more than 1,500 acres in Willapa Bay and 500 acres of Grays Harbor. That’s less than 2% of the total area of the bays.

The most likely application will be from the air, during low tides, using helicopters to directly spray right on the shrimp burrows. Our rules prohibit any spraying during high tide, and when winds are stronger than 10 miles per hour to minimize drift.

Applying the treatment at low tides directly targets the shrimp in their burrows. When the tide comes in, any residual material will be adequately diluted.

Reducing pesticide use by 95% -- less toxic and more effective

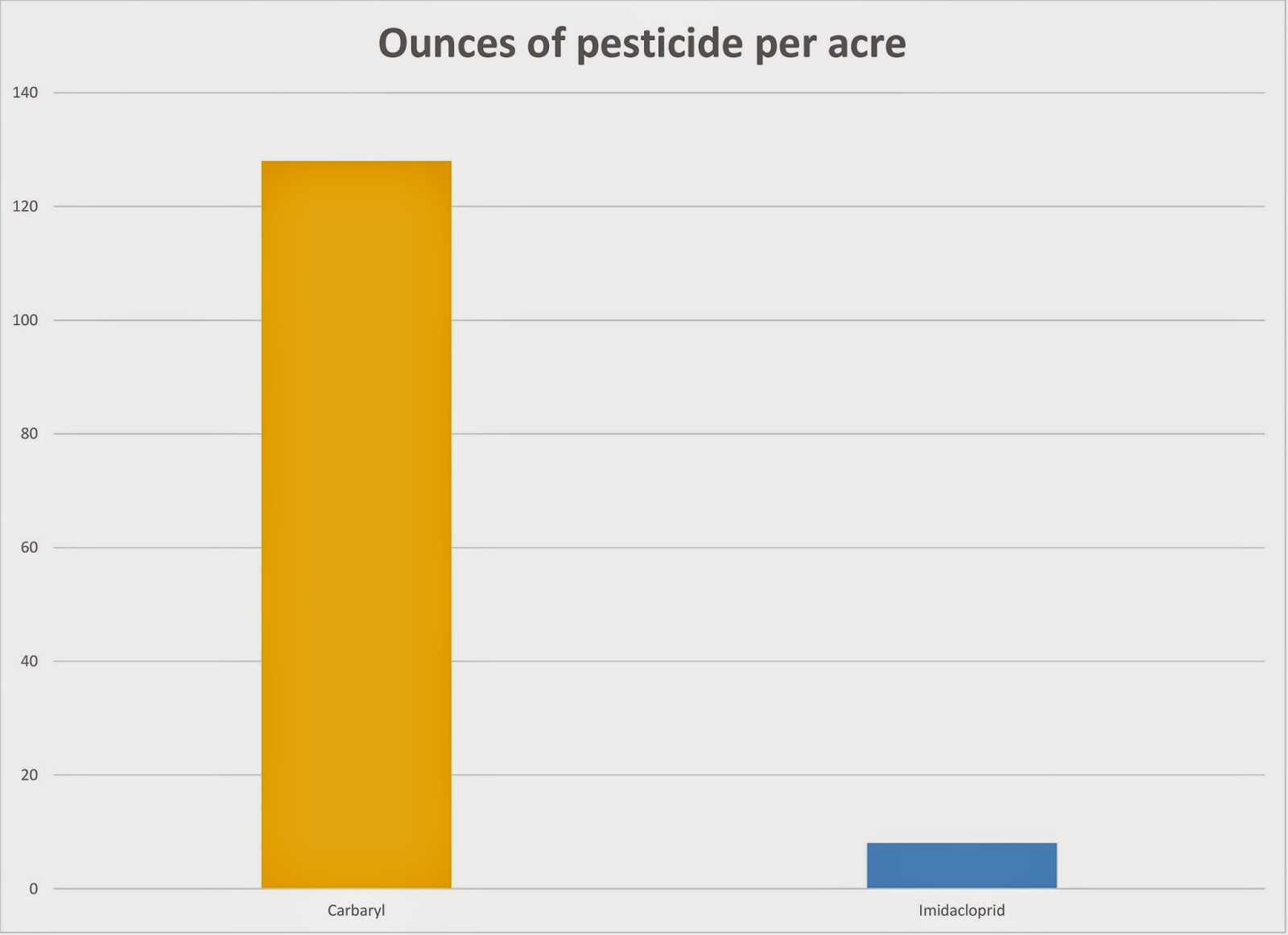

The previous pesticide used by shellfish growers, carbaryl, was applied at a rate of 8 pounds per acre. The new permit issued for imidacloprid limits application to 8 ounces, and it can only be applied once per year.

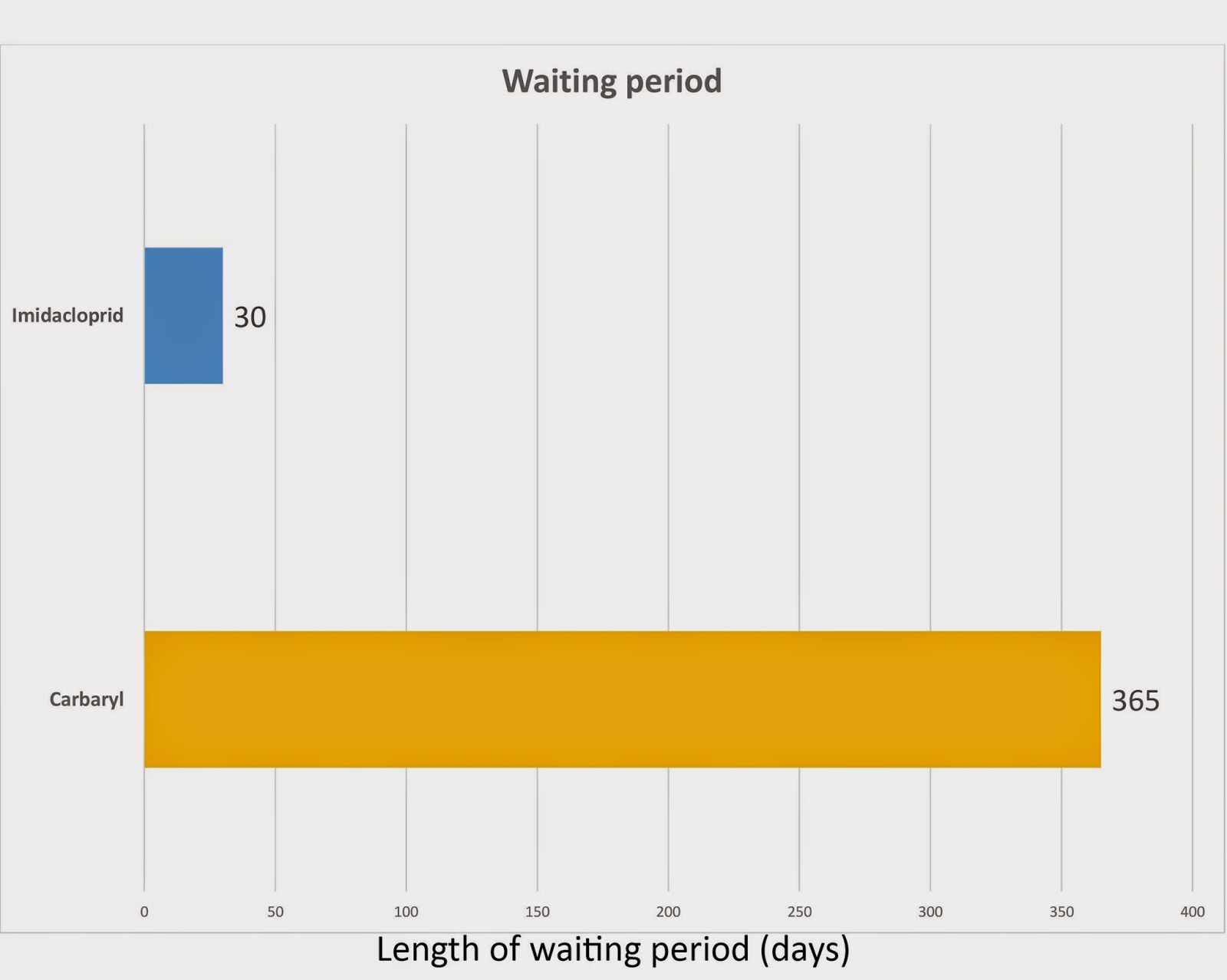

Additionally, the U.S. EPA says that oysters are safe to harvest just 30 days after a treatment of imidacloprid – instead of having to wait an entire year after a treatment of carbaryl.

In our testing we’ve found that the most sensitive creatures that live in the mud, known as benthic invertebrates, return to normal levels just two weeks after a treatment.

Studies and public process

With its widespread use in agriculture, imidacloprid has been studied extensively for use on land. But this is the first time it’s being permitted for use on shellfish beds, and we undertook an extensive scientific review and public involvement process.

We began studying the effects of imidacloprid on water quality five years ago (in 2010). We started the environmental impact study process in January 2014, and held a public meeting in South Bend in February. Public comments have helped shape what was included in our draft Environmental Impact Study (EIS) released in October 2014. The final EIS was released last month.

Everything throughout the process was posted on our website:

Monitoring

The permit we issued on April 16 is valid for five years. It includes monitoring requirements, and the WSU Long Beach Extension is supporting some of the sampling required this year. Over the next five years, we’ll review the annual monitoring data, and identify any adverse impacts to the sediment in the bays and water quality.

If for some reason the effects don’t match our scientific findings, we included conditions to reevaluate the permit at any time.

For some it may seem counter intuitive – the state’s environmental agency allowing the use of a pesticide on shellfish beds. But our job is to protect the water and environment for all of us in Washington. If there’s an opportunity to reduce toxics in the water, we’re going to take it, and that’s what this permit does.