The answer to this riddle is the glistenworm, a beautiful little creature with a complicated past.

Mistaken identity

If you couldn’t solve the puzzle above, you’re in good company — when they were first discovered in 1844, glistenworms had even the experts stumped! Originally they were thought to be sea cucumbers, and were classified in the phylum Echinodermata. It wasn’t until many years later that they were moved to the phylum Mollusca, which includes clams and snails, and put into their own group — the Aplacophora.

There are over 55,000 species of molluscs in the world but only about 390 species make up the small and understudied aplacophoran group. Of these, only one species, Chaetoderma argenteum, has been properly documented to exist in Puget Sound.

No shirt, no shells, no problem!

Typical molluscs create outer shells by secreting minerals from their mantle, a fleshy tissue that surrounds the body and lines the inner surface of the shell. Even some molluscs that appear shell-less, like slugs and squids, have varying degrees of hard structures inside their bodies — reduced or “vestigial” shells that no longer serve much of a function. TOP: Clusters of spicules from C. argenteum BOTTOM: A few individual spicules from C. argenteum have a characteristically 'bent' appearance

Aplacophorans, however, do things differently than their fellow mollusc brethren. Cylindrical and worm-like, they don’t come with a pretty shell that one might find washed ashore on Puget Sound’s rocky coastline, or even an internal shell remnant.

In fact, they are so completely shell-less that they are often referred to as the Naked Molluscs. Instead, they have an outer cuticle embedded with thousands of tiny spines, or spicules, which give them a brilliant shine. This fuzzy-looking exterior layer is practical as well as pretty, presumably making them less palatable to predators.

Getting off on the wrong foot

Many molluscs use a muscular foot for locomotion, and while some aplacophorans do creep around on a simplified, vestigial foot, others have no foot at all. Fortunately, they don’t need to go far. Aplacophorans are exclusively marine bottom-dwellers and spend their time feeding on small organisms in and around the sediment. (Some can even act as parasites on hydroids and corals.) C. argenteum, an example of the footless variety, burrows into the sediment by digging with the shield around its mouth.

LEFT: The mouth of C. argenteum is surrounded by a cuticular oral shield used for burrowing. RIGHT: The posterior end has a single hole used for both reproduction and excretory purposes.

Who’s who?

Taxonomists worldwide have developed several unique methods to help identify these faceless creatures. One method is to examine the ridges and color patterns of the spicules. To do this, we scrape some spicules from a particular part of the animal’s body and examine them under a light microscope with polarizers. Under the polarizers, the spicules produce bands of rainbow colors, which are compared to charts relating to differing species of aplacophorans.

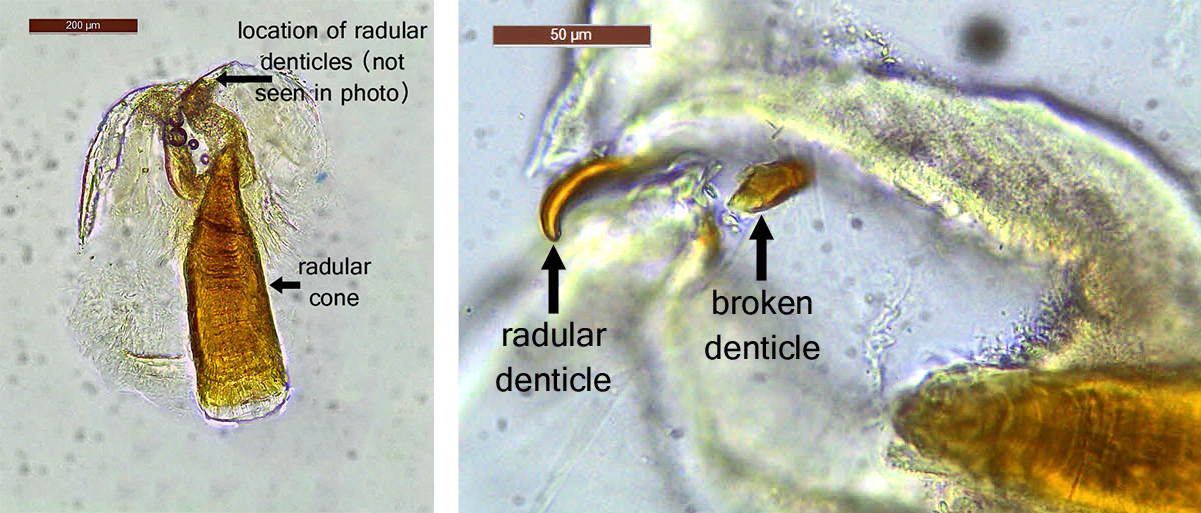

LEFT: The chitinous radula of C. argenteum RIGHT: Close-up of sickle-shaped radular denticles

Another identification method is to dissect and examine the radula (a tooth-like feeding structure that many molluscs possess). We start by cutting off a piece of tissue from the animal’s head closest to its oral shield and mounting it on a slide with some bleach solution. The bleach dissolves the soft tissues and leaves the chitinous structure of the radula intact.

We then use a compound microscope to compare the tiny radula to pictures found in the literature to determine the species identification. Parts of the radula are especially scrutinized including the radular denticles and the radular cone.

Critter of the month

Our benthic taxonomists, Dany and Angela, are scientists who identify and count the benthic (sediment-dwelling) organisms in our samples as part of our Marine Sediment Monitoring Program. We are track the numbers and types of species we see in order to understand the health of Puget Sound and to detect changes over time.

Dany and Angela share their discoveries by bringing us a Benthic Critter of the Month. These posts will give you a peek into the life of Puget Sound’s least-known inhabitants. We’ll share details on identification, habitat, life history, and the role each critter plays in the sediment community. Can't get enough benthos? See photos from our Eyes Under Puget Sound collection on Flickr.